This chapter covers about 200 years of the Johnson Family in the inner East of London. It includes the birth of my grandfather Thomas in 1885 and concludes with the death of his mother Alice in 1947.

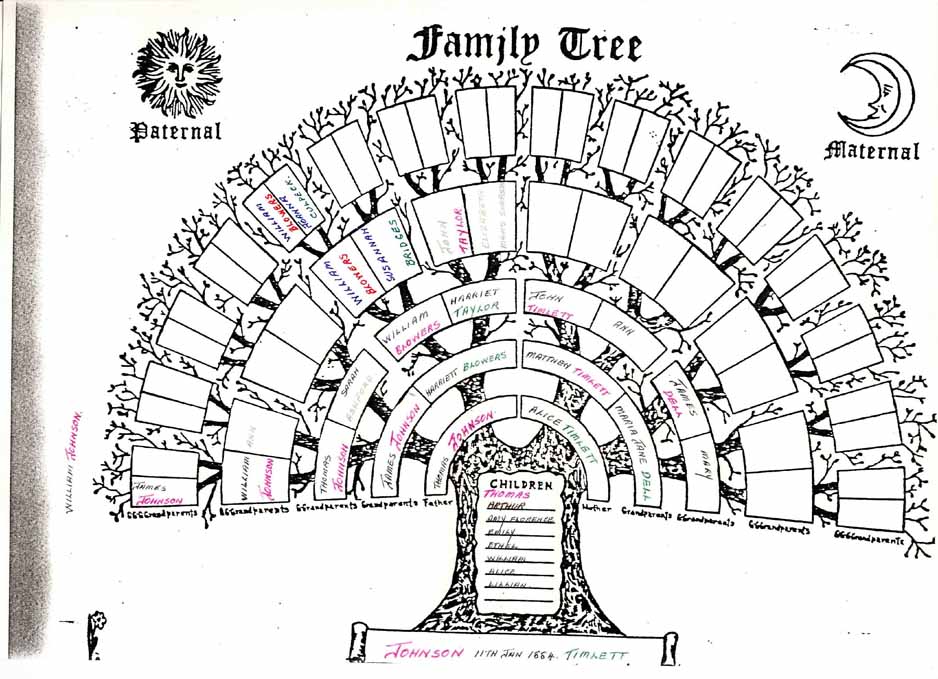

This is a Family Tree that Esme, my mother, drew up in the 1980s. That’s my father’s father, Thomas, at the top of the trunk. Check out where he fits into my family tree on the But First page of this site. Thomas Johnson, as I knew him was a retired shoe salesman, and his connection with the clothing industry goes back a long way. Esme’s research took her to The Clothmakers’ Company – she found out a lot and wrote the following as an introduction:

I wonder if you know that our furthest back ancestor Johnson was one James, son of William [a labourer], who on 7th October 1735 was apprenticed to Daniel Holbrow a cloth worker, he was sworn on 9th October, 1735, and was released of his apprenticeship on 3rd November 1742 to become a Free Man of London in the Clothworkers Company of Dunster Court, Mincing Lane, London.

I was keen to find out more about this Company and was delighted to find it still exists, has a mascot known as Cedric the Golden Ram and a website which proudly announces:

THE CLOTHWORKERS’ COMPANY

“an ancient Livery Company with a rich textile heritage”

James became a “Freeman of London” by successfully completing his apprenticeship with the Company, one of the craft guilds of the time. I found out more about these guilds

From the twelfth century onwards various craft guilds were established in the City of London. Many were associated with religious fraternities and were formed to ensure a decent burial and the saying of Mass for the souls of their deceased members. On a practical level, the guilds or ‘misteries’, from the Latin word for craft, skill or trade, regulated their respective trades, deciding who could work, their wages, working conditions and welfare, and the quality of work and the prices charged. In return for guaranteeing good workmanship and fair prices, a guild was granted a monopoly over its profession and its members wore a distinctive uniform or livery.

James’ sons and daughters and their descendants were then able to claim “Freedom” by inheriting it from their father[s] under certain rules. It was important to claim freedom apparently – my grandfather Thomas was said to have been very put out that his father, also Thomas, never claimed his “Freedom” thus preventing the younger Thomas from doing so. More of this later.

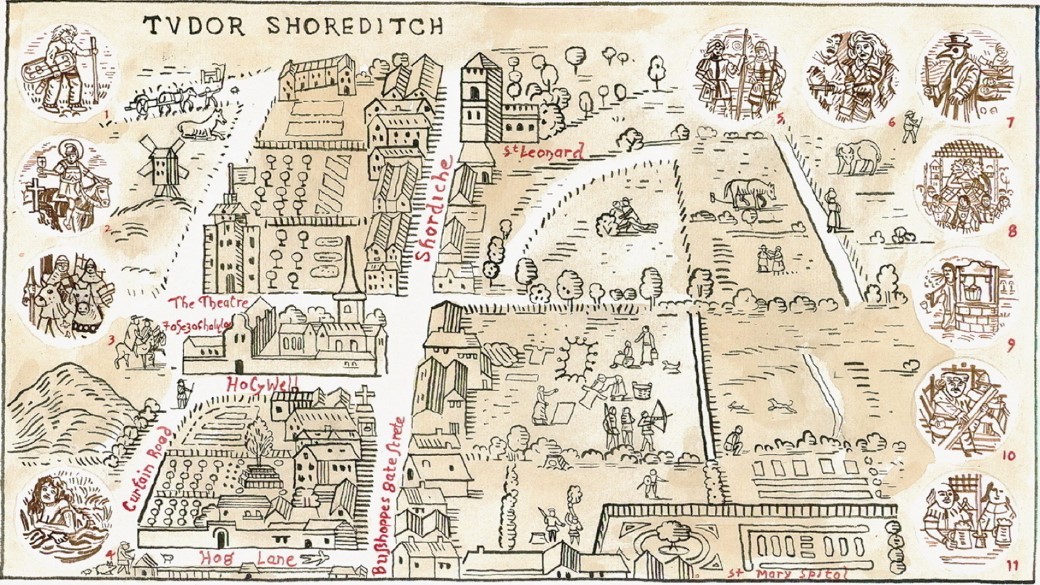

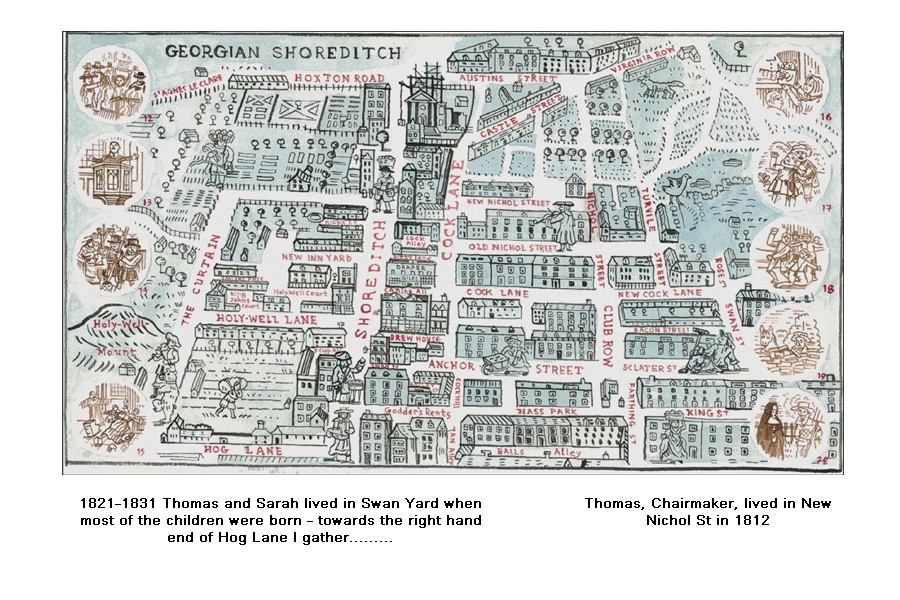

The records of the company were very useful and helped us track the family through the East End of London from the 1730s starting in Shoreditch. I don’t know whether the Johnsons would have identified themselves as Cockneys or not but I did find some maps that help to sketch the history of the community they lived in. Here’s the first:

This map sketches Shoreditch in Tudor times [late 1400s to early 1600s]. We don’t know specifically about any Johnsons here then but in the late 1700s early 1800s there are family members living near Bishopsgate Street and some up closer to St Leonards…….I found the list of historic references that went with the map quite interesting:

1. Iron Age Man establishes a track along what is now “OLD STREET”. [Not on this map]

2. Christian Roman Soldiers worship at the source of the river Walbrook, now St Leonards.

3. Sir John de Soerditch rides against the French Spears alongside The Black Prince.

4. Jane Shore, a goldsmith’s daughter & lover of Edward IV dies in “a ditch of loathsome scent.”

5. “Barlow” the archer is given the dubious title “Duke of Shoreditch” by Henry VIII.

6. Christopher Marlowe murders the son of a Hog Lane innkeeper, he escapes prosecution.

7. Plague burials take place at “Holywell Mound” by the Priory of St John the Baptist at Holywell.

8. Queen Elizabeth I on passing by medieval St Leonards is “Pleased by its Bells.”

9. The sweet water of “The Holywell” is spoilt by manure heaps of local nursery gardens,

10. James Burbage’s sons Cuthbert & Richard dismantle “The Theatre” in two to four days & transport it to the South bank of the Thames where it is rebuilt as “The Globe”.

11. William Shakespeare enjoys a “bumper” at an inn on the site of the present “White Horse.”

THE JOHNSONS in GEORGIAN TIMES

Back to the family starting with James the Clothworker:

1742 James, son of William, gained his Freedom as a Clothworker

1776 William, a Carver, son of James, claimed his Freedom

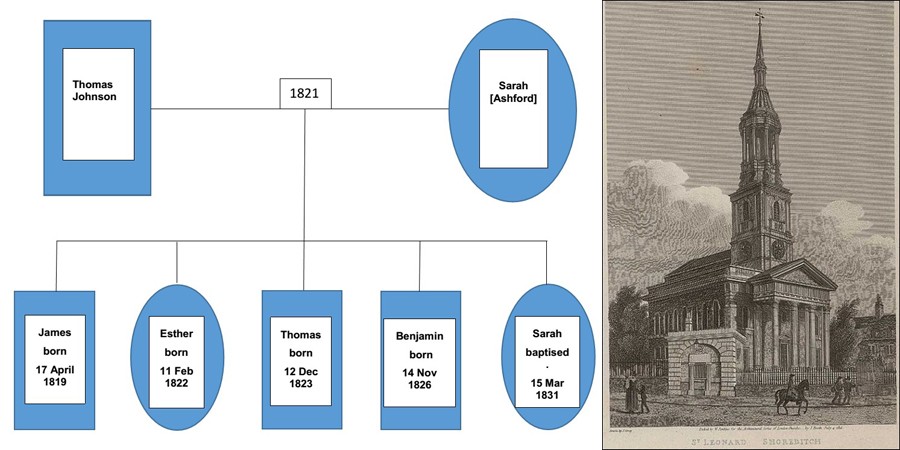

1812 Thomas, a Chairmaker, son of William, claimed his Freedom. At the time he was living at 5 New Nichol St, Bethnal Green. On 23rd September 1821 he married Sarah Ashford. They were “both of the parish”. The marriage was at St Leonard’s Shoreditch conducted by Robert Crosby, curate, and witnessed by John Price and Clifford Elisha.

Sarah was the first Mrs Johnson that we know anything of in this story. She and Thomas [the Chairmaker] had five children that we know of, most of whom were baptised in St Leonard’s.

‘When I grow rich’ say the bells of Shoreditch.

The bells in this nursery rhyme come from St Leonards church Shoreditch and it’s around here that our Johnson family was based for most of the next 60 years or so. From 1821 to 1831 Sarah and Thomas and their children lived at Swan Lane – just a few streets away from New Nicholl St. Things have changed quite a lot in the area as depicted in this Georgian era map and set of notes. St Leonards at the top of the map close to Hoxton Road is being remodelled for a start:

The notes for these times in the area:

12. Local Huguenot weavers riot for three days protesting against & burning “multi-shuttle looms”.

13. Thomas Fairchild, a gardener, donated £25 to St Leonards for an annual Whitsunday sermon titled “Wonderful Works of God in creation” or “On the certainty of resurrection of the dead proved by certain changes of the animal and vegetable parts of creation.”

14. Militia are called from the Tower to quell four thousand Shoreditch locals rioting against cheap Irish labour being used to build the new George Dance tower of St Leonards.

15. Large lumps of masonry fall onto the congregation during a service at the collapsing old St Leonards.

16. The Huguenot speciality “fish & chips” appear at Britain’s first fish & chip shop on Club Row.

17. The many murders & muggings at Holywell Mount lead to it being levelled.

18. Local theatres such as The Curtain sink to become “no more than sparring rooms.”

19. Brick Lane takes its name from local brickfields, occasional location of furtive criminality.

20. Visitors to James Fryer’s land at Friar’s Mount wrongly assume a monastery stood there.

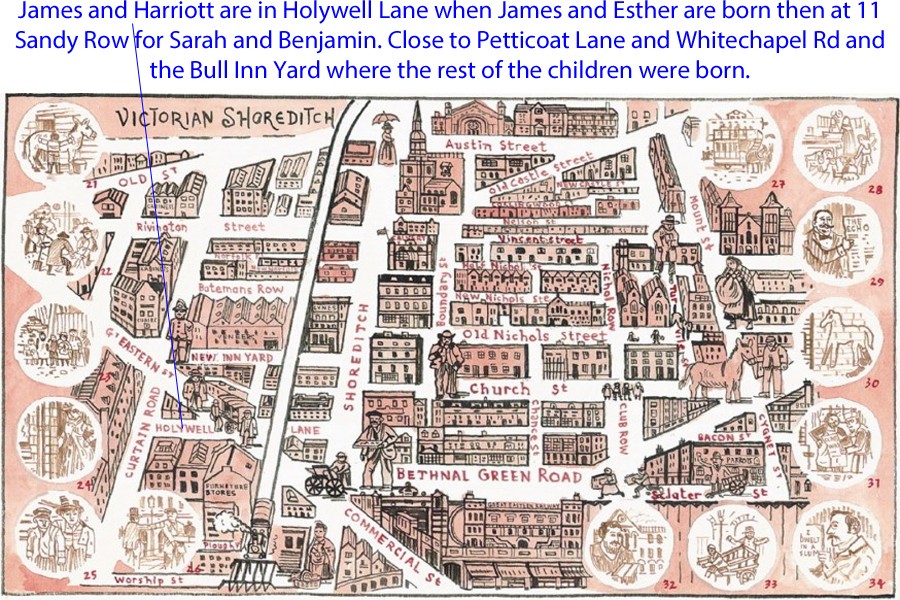

THE JOHNSONS in VICTORIAN TIMES

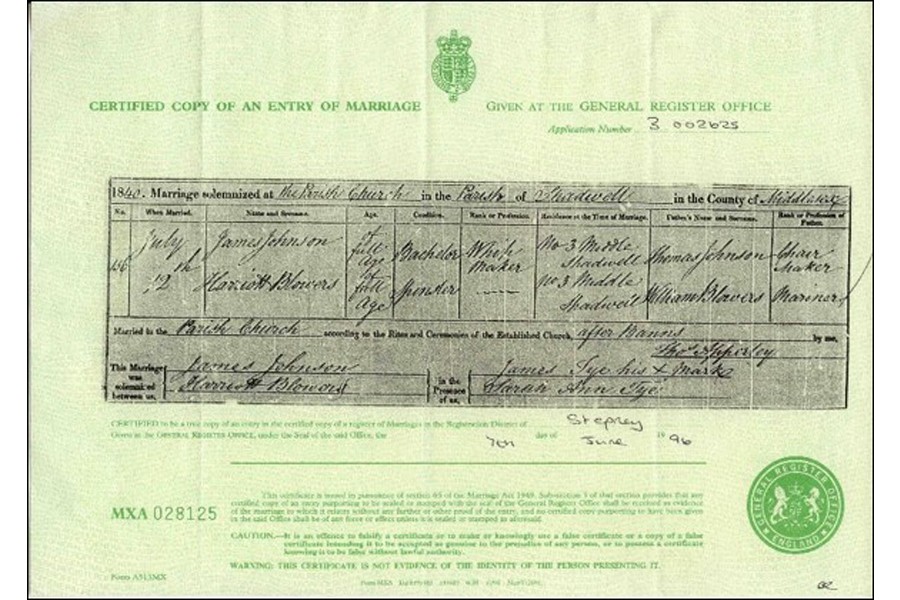

We don’t know anything about the lives and families of Esther, Thomas, Benjamin and Sarah Johnson the four younger children of Thomas the Chairmaker and his wife Sarah Ashford, perhaps someone somewhere is researching them. But we do know quite a bit about their eldest child James. He grows up and becomes a Whipmaker by trade.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert weren’t the only couple married in London in 1840. In that same year, just five months later and about 4 miles down the River Thames, James Johnson, Whipmaker, married Harriott Blowers at St Paul’s Parish Church in Shadwell. At the time of their marriage they were living at No 3 Middle Shadwell and Harriott’s father William Blowers was a Mariner. Middle Shadwell was part of the London Docks at Wapping. These days Shadwell Basin is a recreation area – once a significant body of water in the London Docks of Victorian times. It’s on the north side of the Thames between the Tower of London and Limehouse.

It’s interesting to see what other information the Certificate offers: Both James and Harriott were ‘of full age’ – he was 21 and she 17.They were both living at No3 Middle Shadwell – was that her parents’ home? He’s listed as a Bachelor, she a Spinster and they were married by Thos Apperley – we meet him again later. James Tye and Sarah Ann Tye were witnesses. James Tye signed with an X – I’m assuming that the others could write. They set up home in Holywell Lane and start having children.

21. Joe Lee, the local horsewhisperer, coaxes improved productivity from working donkeys.

22. “Resurrection Men,” notorious body snatchers pinch recent interred corpses from St Leonards,

some coffins in the crypt are found to contain bricks instead of bodies,

23. Four thousand people are dispossessed as Bishopsgate Goods Yard replaces streets around Swan Lane & Leg Alley.

24. Mary Kelly’s funeral procession leaves St Leonards amidst huge crowds. The poor victim of Jack the Ripper is given a second funeral at her own catholic cemetery.

25. Oliver Twist is said to have resided in Shoreditch. Many other unfortunate children arrive

each morning at The White St Child Slave Market seeking work.

26. So many unruly pavement-side street vendors populate

Shoreditch High St that a regular uniformed Street Keeper is employed.

27. Horse drawn trams add to the general commotion bustle and smell of the High Street.

28. Cats meat sellers, watercress hawkers & dog breeders all cram into the Old Nichol’s filthy tenements.

29. Sir Arthur Arnold, head of the LCC main drainage committee is commemorated at Arnold Circus.

30. For decades the chalk horse on Bishopsgate Goods Yard is redrawn by unknown local artist.

31. Enthusiastic Anarchists hoping to bring political awareness to the Old Nichol proletariat through their Boundary St printing operation find the task “like tickling an elephant with a straw.”

32. Artist, Lord Leighton calls the interior of Holy Trinity, Old Nichol St, “The most beautiful in England.”

33. Arthur Harding’s memories of his slum boyhood, “van dragging” etc are recalled in “East End Underworld.”

34. Arthur Morrison pens his slum tale “Child of the Jago” following Reverend Jay’s invitation to the Old Nichol.

http://spitalfieldslife.com/2010/07/19/adam-dants-map-of-shoreditch

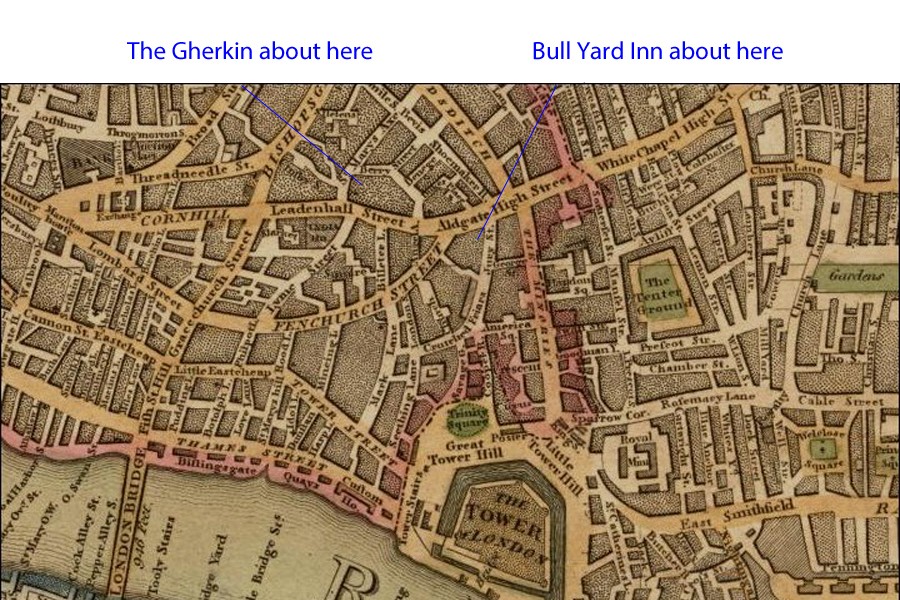

It seems that James and Harriott’s two oldest children may have died as infants – there’s no mention of them in any of the later census papers. By 1850 the rest of the young family had moved to live and work in the Bull Yard Inn in Aldgate and by 1863 there were seven surviving children that we know of. The youngest was Thomas and he grew up to be a Car Man, later a Beer Retailer, later our great grandfather. More of him anon but first let’s find out more about Aldgate and the Bull Inn Yard.

THE BULL INN YARD ALDGATE

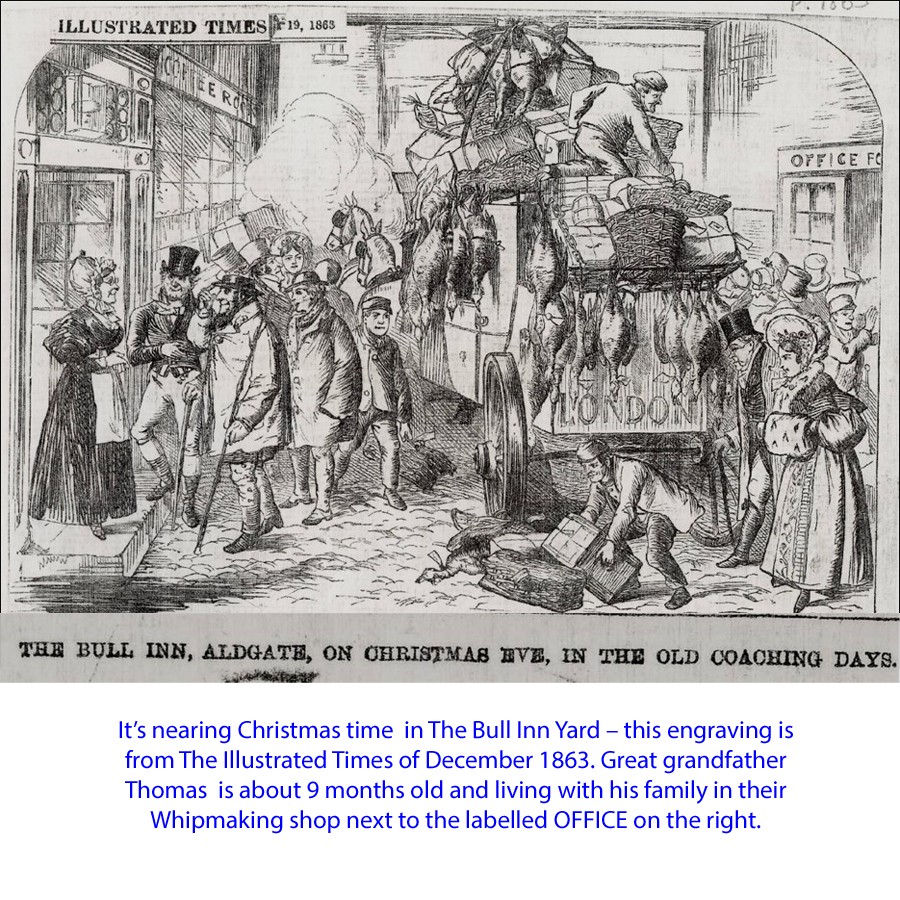

I can only imagine how excited my parents were when Mum found this engraving from the Illustrated Times. Great grandfather Thomas was a baby at the time it was published, his next brothers up, William and Benjamin were 8 and 9. Older sibs James and Esther were in their teens. This scene would have been familiar to them presumably. Perhaps they read the accompanying article:

I can only imagine how excited my parents were when Mum found this engraving from the Illustrated Times. As well as Thomas there were his next brothers up, William [8] and Benjamin [9]. Older sibs James and Esther were in their teens. This scene would have been familiar to them presumably. Perhaps they read the accompanying article:

THE GREEN OLD AGE OF A LONDON INN

A MAN who has spent a great part of his life in the City maintains a loving acquaintance with certain old nooks and corners which have not been reached by modern innovations. Quite away from ordinary commercial interests, and lying quietly apart from the bustle and traffic of the crowded streets, there are all sorts of quaint places associated in his mind with a score of romances, half true, half imaginary, which are suggested by the queer, dingy, faded mansions, the little dim churches, the blank churchyards [tanks of dead leaves and grass-grown tombs], the sooty trees, and the silent courtyards on which a cool shade rests even at noon in July. Not the least suggestive of all the old by-places in London are those wonderful old City inns which may be discovered here and there, their great yards staring blankly for the coaches which will never come; their wooden galleries, surrounded with bedroom-doors, looking out over the space which would be empty but for a country waggon or two; their coffee-rooms, the resort of men who are here to-day and gone to-morrow, gone not by the brightly-gleaming, fast coach, with its four horses, prancing out under the archway as the stable helper leads them into the street, but by the railway omnibus which meets five trains a day.

The British coachman, as he was described by Washington Irving in 1820, would be totally unknown to the younger members of our community but for his lifelike presentation in the pages of “Pickwick,” where his appearance and peculiarities are recorded by the great novelist. In no quarter of London was he better known that at the good old Inn represented in our Engraving; for it stood then, and, indeed, stands still, in the great highway of the metropolis – the main artery of England. We have always been of the opinion that a voyager round the globe, who started fair and kept an even course, would ultimately turn up in the Mile-end-road, and so come on towards Aldgate; and it is in the latter place that the Old Bull Inn still stands – if not in its glory, at least in a very green and vigorous condition. Its glory, indeed may be said to have departed rather less than a score of years ago, when the railways practically superseded the mail coach and the “four spanking tits,” on which our fathers were so eloquent. Before this time “The Bull” was the centre of the coaches running the long journeys on the Norfolk road, besides being the station of a number of those which journeyed to the northern and western towns.

It is an unpretentious place enough; not galleried, as some of its contemporaries are, but containing at the end of its long and rather narrow entrance a large space, surrounded by the stables; the inn itself lying on the left, and the various offices on the right of the passage. Yet this modest-looking hostelry was a place of great importance when its square yard resounded with the bustle and excitement of arriving and departing passengers, and the constant succession of green and drab coated, florid men, with a “power of suction” worthy of the elder Mr. Weller, and a decided taste for ale, corned beef, and lukewarm brandy-and-water.

It was at Christmas-tide, however, that the Bull Aldgate, was at its best, when the coaches came in from the country loaded with presents, mostly in the form of poultry, game, and other edibles; but [so many coming from Norfolk] notably of turkeys. Then brisk chambermaids and distracted waiters were at their wits’ end to provide for hungry and tired guests; then ostlers and stable helps hissed and curry-combed, and hauled here and unbuckled there, and shouted till the inn yard was in an uproar. And still the coaches came with more parcels, till stables had to be given up to baskets and packages, while the turkeys were piled in stacks or hung from rack and manger, a glorious sight to see.

Nearly six hundred horses were employed by the present host of the Bull to supply some of the stages for his coaches in various parts of the country. Of all those six hundred not six remain; for the railways came, and, skirting the great highway without stopping at the old resting- place, left the vehicles to drop off the road, and the ruddy, shawl-wrapped coachmen to disappear as they might, their occupation and their characteristics to die out for ever. The old inn stands there yet, however, accommodating itself as it best can to its altered circumstances, and blossoming in a quiet and a green old age. It is true that its entrance is placarded, not with the bills announcing the times of departure of fast coaches, but with railway time-bills and the notices of special trains;

But there are still horses baiting in its spacious stables, the whipmaker on the right-hand side of the entrance still shows a goodly stock in his low window, the booking office is bright with the glow of gas, and there is still evidence of what was once the harness-room. Only a few waggons, carts, and chaises visit the yard; and some of the former are but railway-waggons calling there for parcels; but in the old coffee-room the fire yet burn brightly, its ruddy glow reflected in the bright mahogany tables, while in the “boxes” snug parties of old stagers, who know a good old inn when they see one, are gathered for confidential talk. About the bar there is still the queer agglomeration of little rooms, each going either up or down a shallow step; and waiters and chambermaids are still there, prepared for any emergency, even [were it possible] for the abolition of railways.

But for the latter [the chambermaids , we mean], it might be said that everything was old and staid; but gallantry forbids us to record any such conclusion.

Whatever may have departed from the old inn, however, its comfort and its homely hospitality seem to be unimpaired – its old cellars still yield some of the good old wine; and the host, one of an old family who have been associated with many of the most celebrated of old London hostelries, is too genial to resent the changes which time has wrought; and so lives, like the inn itself, with the prospect of a green and sound old age.

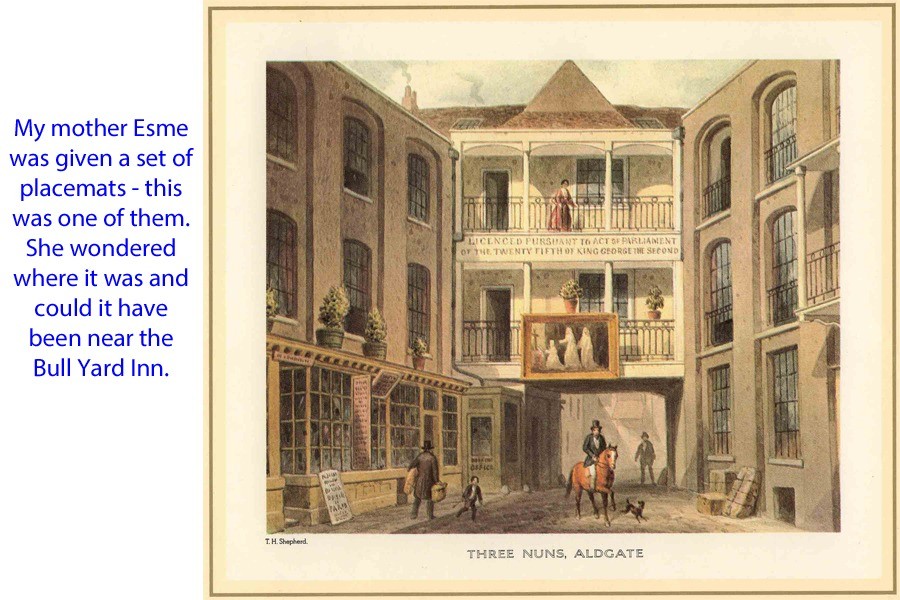

Mum used the internet in her later years but most of it was a mystery to her. She would have been delighted if we had found these sites that suggest that the Three Nuns and the Bull Yard Inn may have nearer each other in time and place than she thought. This next bit from some of these sites: